Friday, December 31, 2010

Thresholds -- the Real Secret of the Super Rich Part 4

As we have seen in this series, the real secret of the super rich is neither positive thinking nor dark forces at work. It is nonlinearity. The basic bell curve distribution comes from adding assorted random variables together, and as we have seen, there is no way to map such a bell curve distribution to the actual wealth distribution of the United States (or probably any other nation). The underlying logic of the bell curve doesn’t even make sense if you think about it. If Bill Gates was a poor programmer or a poor businessman, he would be simply half as rich. He would not be rich at all. (Or at least not rich as a software entrepreneur.) These factors multiplied each other.

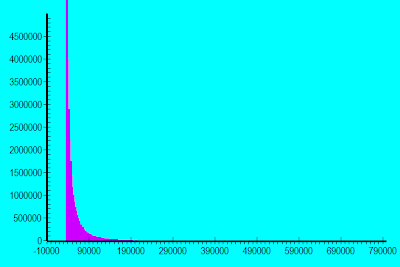

I modeled the effect of multiplying abilities/drives/luck factors together in Part 3. To review, here is the graph I get when I take five random factors, multiply them together and normalize to match median household income and a standard deviation which divides the bottom two quintiles properly.

We get a nice bulge near the median and a tail off to the right, but we still don’t get any super rich people. My model estimated only 56 people barely breaking a half million people per year. (This estimate is quite noisy; only one dice roll out of a million landed in this bin.)

Let’s think back to our Bill Gates model. If he was half as good a programmer, he wouldn’t simply have had half as good a business; he wouldn’t have gotten into writing interpreters and operating systems at all. If his parents had been half as well off, he wouldn’t have had half the practice writing software as a child. He would have had none at all. If he had too little interest/ability in business, he would have stayed in Harvard and probably became an academic or high paid programmer working for someone else. For many of the factors which went into making Bill Gates rich, there is a threshold value below which his life would have followed a very different trajectory.

And above the thresholds, the difference between good and great were still enormous. Had he and his friends done a less good job writing BASIC interpreters, Microsoft would have been just another flash in the pan software house. Gates and company abstracted out the hardware dependent portions of their interpreter so they could have a new interpreter ready for each new machine faster than any competitor or in-house programmers could. Microsoft got big because they were very competent – combined with a willingness to compromise quality in order to make computing affordable.

Since dealing with multiple operating systems is quite a bother for both customers and software designers, operating system design is a winner-take-all business. The difference between best and second best is huge, and the difference between best the fourth best is truly enormous. Similar economies apply to radio and pre-cable television. Ditto for sports. When the number of niches is few, those who win win big.

To model these dynamics simply, I took the code from my previous experiment and squared the rolls for the individual factors. That is, for each factor I rolled 5 twenty-sided dice, added the results together and squared the total. Then these factors were multiplied together as before and the results renormalized to match the target median and standard deviation. The result was:

Now we are getting somewhere: heavy clustering around the middle with a tail off to the right. When I look at the underlying chart, my top nonzero bin is now at 1.5 million dollars per year, and I have four bins breaking a million dollar income with an estimated 500 people per bin. This is still too low, however, so I then tried cubing the factors to get:

This gets me a top bin of around four million dollars per year, but only 50 people in that bin. The model is better, but still doesn’t fully account for the super rich. I could get more aggressive yet (worth doing for winner-take-all economics) or play with more input factors (talents, drive, luck,etc.) but I have another nonlinearity to cover in the next post.

Also, the two curves above don’t go down far enough. We get some rich at the cost of losing the working poor. A higher-fidelity model would take into account the fact that there are two economies: one with high barriers to entry and winner-take-all economics and another where gain is linear or less with effort; i.e., the ordinary wage and Main St. economy.

This post is running long, so I’ll leave it primarily as a meditation for the reader to figure out how to apply the knowledge above. Here are a few hints.

If you want to get really rich, look for barriers to entry and cross them. In other words, don’t look for the free money making opportunities. Those lead to mediocre incomes unless you happen to be lucky enough to get in early. Low barrier to entry income can be good for seed money and gaining experience, but the real bucks must come from beating out some real competition.

If you don’t like the enormous wealth gap we have today, you have two ideas you can apply. First, look to lower barriers to entry. This requires going against the modern liberal impulse to craft complex legislation that only an expensive lawyer can understand. If going into a business requires expensive legal and/or engineering consultants, only people who can afford these expensive professionals will be able to compete. Second, look to divide up the economy into more independent niches. For example, federalizing intrastate commerce law gives economies of scale to multi-state corporations such as Wal Mart. Having different laws in each state gives smaller operations a fighting chance.

But neither of these paths will bring the wealth gap down to liberal targets unless we deal with the final nonlinearity: the rich get paid just for being rich. I’ll explain more in the next post.

Sunday, December 12, 2010

Abilities Chosen -- Effects on Wealth Distribution

I'm baaaack! Sorry it took so long. I've interrupted my study of the super rich to work on a project to efficiently get free money to the poor. (Our current welfare system is inefficient and encourages bad behavior.)

Anyway, in part 3 of my series on the secret of the super rich, commenter Paul suggested I look at the effect of selecting which abilities to employ. That is, Bill Gates did not employ his atheletic abilities to build Microsoft. In fact, limits to athletic ability may have helped since he wasn't distracted in high school by playing football and chasing cheerleaders. True, if he had been severely handicapped athletically, a la Stephen Hawking, he might have had less success. But otherwise, this ability did not particularly factor in.

But it has factored in for many other successful people.

So, maybe it's just a matter of choosing several strengths to put together in order to become a member of the super rich. To test this hypothesis, I looked at multiplying together the best of several distributions. That is, in the previous post I looked at multiplying five abilities together, which each ability was a distribution generated by 5 20 sided dice. The result was:

(This time around I have rescaled my graphs by the bin size, creating proper distributions. The units are population per $1000 income range.)

Now, let's take our five best abilities from among ten abilities rolled with the same distribution. The result is:

Unless I made a programming error, allowing people to pick a subset of available abilities to multiply together reduces the outliers to the right. Yes, when I take the raw numbers, I get more high rolls, but once scaled to population, median income and standard deviation, I end up with a gentler slope on the left side of the curve. The right tail is a bit fatter, but doesn't go out as far.

Unless I made a programming error, allowing people to pick a subset of available abilities to multiply together reduces the outliers to the right. Yes, when I take the raw numbers, I get more high rolls, but once scaled to population, median income and standard deviation, I end up with a gentler slope on the left side of the curve. The right tail is a bit fatter, but doesn't go out as far.

In other words, abilities chosen, even when multiplied, produces a curve that fits intuitive notions of a meritocracy and not the huge outliers to the right that we see in real life.

Of course, not everyone chooses their best abilities. If the super rich do choose to exercise their best abilities while others allow the whims of fate to set their careers, this might explain some of the wealth gap. But I think other factors are at work. Hopefully, I'll get around to explaining them in a timely fashion.

Anyway, in part 3 of my series on the secret of the super rich, commenter Paul suggested I look at the effect of selecting which abilities to employ. That is, Bill Gates did not employ his atheletic abilities to build Microsoft. In fact, limits to athletic ability may have helped since he wasn't distracted in high school by playing football and chasing cheerleaders. True, if he had been severely handicapped athletically, a la Stephen Hawking, he might have had less success. But otherwise, this ability did not particularly factor in.

But it has factored in for many other successful people.

So, maybe it's just a matter of choosing several strengths to put together in order to become a member of the super rich. To test this hypothesis, I looked at multiplying together the best of several distributions. That is, in the previous post I looked at multiplying five abilities together, which each ability was a distribution generated by 5 20 sided dice. The result was:

(This time around I have rescaled my graphs by the bin size, creating proper distributions. The units are population per $1000 income range.)

Now, let's take our five best abilities from among ten abilities rolled with the same distribution. The result is:

Unless I made a programming error, allowing people to pick a subset of available abilities to multiply together reduces the outliers to the right. Yes, when I take the raw numbers, I get more high rolls, but once scaled to population, median income and standard deviation, I end up with a gentler slope on the left side of the curve. The right tail is a bit fatter, but doesn't go out as far.

Unless I made a programming error, allowing people to pick a subset of available abilities to multiply together reduces the outliers to the right. Yes, when I take the raw numbers, I get more high rolls, but once scaled to population, median income and standard deviation, I end up with a gentler slope on the left side of the curve. The right tail is a bit fatter, but doesn't go out as far.In other words, abilities chosen, even when multiplied, produces a curve that fits intuitive notions of a meritocracy and not the huge outliers to the right that we see in real life.

Of course, not everyone chooses their best abilities. If the super rich do choose to exercise their best abilities while others allow the whims of fate to set their careers, this might explain some of the wealth gap. But I think other factors are at work. Hopefully, I'll get around to explaining them in a timely fashion.

Thursday, January 7, 2010

Abilities Multiplied -- The Real Secret of the Super Rich Part 3

(This is Part 3 of The Real Secret of the Super Rich.)

In Part 2 we saw that bell curve distributions arise when we add several independent random variables together. They can be coin flips, dice rolls, or the luck factors or choice factors which arise in real life. When we tried to map some computer generated experiments based on this model with the real world wealth distribution in the U.S. we came up short. There were no incomes which could lead to billionaire status in one lifetime.

Perhaps the model is wrong; perhaps we shouldn't expect a bell curve income distribution. Consider Bill Gates. He was very intelligent, interested in computers, and interested in business. He had access to computers as a child when very few others did, and he had a well-off family to support him when he launched his business; he did not have to sell off parts of the company early on. I could list more abilities, circumstances and personal choices which led to his billionaire status, but let's just stick to these five. Do they add up?

Do they add at all? Could a stupid person interested in computers write a BASIC interpreter? Would a brilliant person uninterested in computers write a BASIC interpreter? Even if that brilliant individual was interested in becoming a billionaire, would he go into programming with a vengeance years before there was real money to be made? Lacking either intellect or interest in computers, Mr. Gates could or would not have taken the paths he did. Overwhelming amounts of either quality could not make up for lack of the other. The abilities multiplied.

Excellence in four out of the five factors did work for some of the early microcomputer pioneers. (See Accidental Empires by Robert X. Cringely.) Many of the early pioneers in the personal computer industry were more interested in computers than business. Since the field was so open, competition was weak -- save for Microsoft, which ate many of the other companies for lunch. But even these relatively uninterested in business players were interested enough in business to start businesses vs. work for the government or academia. They just didn't play as cutthroat as Bill Gates. So the multiplier model still applies.

I extended the program I used for Part 2 to allow multiplying distributions together. Let each of the five qualities for Bill Gates be modeled by five twenty-sided dice. (I went for dice instead of coins because when multiplying, zero values have a huge impact. If we get zero for any quality, then the product is zero.) Then for each round, we roll the five dice, add the result and do so again four more times and multiply each result together. Do so a million times and you get this:

Rescale to the median and standard deviation of the U.S. income distribution and we get the following. (The y value scales to the bin size I used, which is much smaller than what I used for Part 2. I should go from bar chart to proper probability distribution, but I'm too lazy.)

Aha! we are getting somewhere! Many people are clumped near the median income, but we have a "fat tail" off to the right: more six figure incomes than a Gaussian distribution would give us. But still, no multi-million dollar incomes. The maximum income for this experiment was $550,000.

Maybe we need to consider more than five factors. Let's try ten:

You cannot tell from the graph, but looking at the raw numbers, we do a bit better. This experiment gave us 116 families making $940,000 per year. Still nowhere near Bill Gates levels of income. Also, the model starts breaking down at the low end: I don't get anyone making less than $18000/year. (Then again, when you factor in welfare benefits, this might be a decent model...)

Our model so far is imperfect, but it significantly improves on the additive model which led to a bell curve. We can apply this multiplier model to both personal performance and policy. So if you are trying to get rich or you're trying to keep the uber-rich from dominating the country excessively, I now have something you can use.

The first thing to take away from the above experiment is that I didn't use every useful human capability, strategy or circumstance to model Bill Gates. I didn't include charm, good looks, political connections, or physical strength. Not all qualities are relevant to all success paths. But most success paths do require more than one quality. Pick a success path which uses several qualities in which you excel and you are on your way.

Here is something to excite the ambitious: consider a success path that is a function of 5 qualities. What happens if through sacrifice and hard work you manage an across the board doubling? Do you double your output? No, you increase your output by a factor of 32! (2 to the 5th power). Keep this in mind when some guru says just focus on your strengths or your passions. If any of your weaknesses come into play in your chosen career path, it still profits you to work on them. Consider the case of the testerone-filled talented athlete from a rough neighborhood. Such an athlete may have a weakness in the anger-management/self-control area. But since jail time or league expulsion can be very expensive for a superstar athlete, effort in this area is still profitable.

That said, it does pay to work on your natural talents first. If you double your performance at any link in the chain, you get a doubling overall. Early on, it is far easier to enhance your natural abilities through practice and study than it is to remedy your weaknesses. However, as time grows on, you will saturate a bit. In absolute terms your greatest opportunities may still be your natural strengths, but in relative terms, working on (relevant) weaknesses becomes more profitable. Fortunately, after your strengths have been developed, the payback for relative improvement in relevant weaknesses goes up, so even if such efforts are still unpleasant, the rewards have gone up.

Many a startup business leader started with a passion for the field he or she worked in. Only after success in developing a product or service did the finer aspects of business management, marketing, etc. become truly interesting. You don't have to go to business school to become a tycoon. Get far enough in a business your are talented and passionate about, you will gain the interest in what they teach in business school -- along with employees/partners from same.

There, I taught those of you who came to this site looking for get rich quick schemes far more than you'll learn from reading The Secret or many other mind-game guru books. Now, for those interested in public policy.

Our public schools were meant to equalize opportunity, to help those children whose parents either cannot afford education or are uninterested in providing it for their children. Any improvement in the public schools is a chance to equalize up, to make the poor richer vs. making the rich poorer.

Now consider the public schools in the light of our success model. Relative improvement in any of the factors leading to success multiplies overall success. Relative improvement is easiest to achieve early on for those areas where the student is naturally interested and/or talented. Only after these areas have been saturated does it really pay to work on weaknesses.

So what do our schools do? They hold back students to the learning rate of their weaknesses. If you excel in math but poor in language, you get held back overall to match your language learning ability. If you are potentially brilliant artist, you still have to wait until high school to take a real art class. (This may not hold for the better schools.) If you are a natural athlete but poor academically, you aren't allowed to play on the varsity squad.

The power-nerd math genius should be taking advanced calculus in high school even as he is still mastering basic social skills and writing. The poet should be taking college level creative writing even as she struggles with basic algebra. The athlete from the ghetto might well take remedial public speaking and finance during the off season during his career years, after dropping out of college to make a multi-million dollar salary.

This doesn't mean the schools should allow children to focus only on their strengths. It means don't spend more time on the weaknesses than the strengths. It means let the talented leap forward in their particular skill areas while they muddle along in their areas of weakness.

Finally a personal application: promoting this very web site. Readership is a function of how many people find it times how interesting it is to them once they get here. Some Internet marketing experts write that I should spend more time promoting the site, getting links and the like, than producing the content itself. And they are right to first order. If I were to write articles elsewhere pointing to this site, commenting on other blogs, etc. readership would be much higher here than by my writing lengthy quality posts based on research and experiment. But I don't like link-building. So I write what I hope is good content (and the repeat visitor stats indicate someone likes this stuff), and spend less time promoting it. Eventually, there will be enough content to make it worth promoting even for me.

But I'm hoping for a higher order effect. If the quality is good enough, some of the visitors will do the linking for me. And if enough do so link, the search engines will bring in yet more visitors. Traffic will snowball. And this, my dear readers, points to two other important nonlinearties. We have more yet to explore regarding the real secret of the rich. Stay tuned.

In Part 2 we saw that bell curve distributions arise when we add several independent random variables together. They can be coin flips, dice rolls, or the luck factors or choice factors which arise in real life. When we tried to map some computer generated experiments based on this model with the real world wealth distribution in the U.S. we came up short. There were no incomes which could lead to billionaire status in one lifetime.

Perhaps the model is wrong; perhaps we shouldn't expect a bell curve income distribution. Consider Bill Gates. He was very intelligent, interested in computers, and interested in business. He had access to computers as a child when very few others did, and he had a well-off family to support him when he launched his business; he did not have to sell off parts of the company early on. I could list more abilities, circumstances and personal choices which led to his billionaire status, but let's just stick to these five. Do they add up?

Do they add at all? Could a stupid person interested in computers write a BASIC interpreter? Would a brilliant person uninterested in computers write a BASIC interpreter? Even if that brilliant individual was interested in becoming a billionaire, would he go into programming with a vengeance years before there was real money to be made? Lacking either intellect or interest in computers, Mr. Gates could or would not have taken the paths he did. Overwhelming amounts of either quality could not make up for lack of the other. The abilities multiplied.

Excellence in four out of the five factors did work for some of the early microcomputer pioneers. (See Accidental Empires by Robert X. Cringely.) Many of the early pioneers in the personal computer industry were more interested in computers than business. Since the field was so open, competition was weak -- save for Microsoft, which ate many of the other companies for lunch. But even these relatively uninterested in business players were interested enough in business to start businesses vs. work for the government or academia. They just didn't play as cutthroat as Bill Gates. So the multiplier model still applies.

I extended the program I used for Part 2 to allow multiplying distributions together. Let each of the five qualities for Bill Gates be modeled by five twenty-sided dice. (I went for dice instead of coins because when multiplying, zero values have a huge impact. If we get zero for any quality, then the product is zero.) Then for each round, we roll the five dice, add the result and do so again four more times and multiply each result together. Do so a million times and you get this:

Rescale to the median and standard deviation of the U.S. income distribution and we get the following. (The y value scales to the bin size I used, which is much smaller than what I used for Part 2. I should go from bar chart to proper probability distribution, but I'm too lazy.)

Aha! we are getting somewhere! Many people are clumped near the median income, but we have a "fat tail" off to the right: more six figure incomes than a Gaussian distribution would give us. But still, no multi-million dollar incomes. The maximum income for this experiment was $550,000.

Maybe we need to consider more than five factors. Let's try ten:

You cannot tell from the graph, but looking at the raw numbers, we do a bit better. This experiment gave us 116 families making $940,000 per year. Still nowhere near Bill Gates levels of income. Also, the model starts breaking down at the low end: I don't get anyone making less than $18000/year. (Then again, when you factor in welfare benefits, this might be a decent model...)

Applying the Secret

Our model so far is imperfect, but it significantly improves on the additive model which led to a bell curve. We can apply this multiplier model to both personal performance and policy. So if you are trying to get rich or you're trying to keep the uber-rich from dominating the country excessively, I now have something you can use.

The first thing to take away from the above experiment is that I didn't use every useful human capability, strategy or circumstance to model Bill Gates. I didn't include charm, good looks, political connections, or physical strength. Not all qualities are relevant to all success paths. But most success paths do require more than one quality. Pick a success path which uses several qualities in which you excel and you are on your way.

Here is something to excite the ambitious: consider a success path that is a function of 5 qualities. What happens if through sacrifice and hard work you manage an across the board doubling? Do you double your output? No, you increase your output by a factor of 32! (2 to the 5th power). Keep this in mind when some guru says just focus on your strengths or your passions. If any of your weaknesses come into play in your chosen career path, it still profits you to work on them. Consider the case of the testerone-filled talented athlete from a rough neighborhood. Such an athlete may have a weakness in the anger-management/self-control area. But since jail time or league expulsion can be very expensive for a superstar athlete, effort in this area is still profitable.

That said, it does pay to work on your natural talents first. If you double your performance at any link in the chain, you get a doubling overall. Early on, it is far easier to enhance your natural abilities through practice and study than it is to remedy your weaknesses. However, as time grows on, you will saturate a bit. In absolute terms your greatest opportunities may still be your natural strengths, but in relative terms, working on (relevant) weaknesses becomes more profitable. Fortunately, after your strengths have been developed, the payback for relative improvement in relevant weaknesses goes up, so even if such efforts are still unpleasant, the rewards have gone up.

Many a startup business leader started with a passion for the field he or she worked in. Only after success in developing a product or service did the finer aspects of business management, marketing, etc. become truly interesting. You don't have to go to business school to become a tycoon. Get far enough in a business your are talented and passionate about, you will gain the interest in what they teach in business school -- along with employees/partners from same.

There, I taught those of you who came to this site looking for get rich quick schemes far more than you'll learn from reading The Secret or many other mind-game guru books. Now, for those interested in public policy.

Our public schools were meant to equalize opportunity, to help those children whose parents either cannot afford education or are uninterested in providing it for their children. Any improvement in the public schools is a chance to equalize up, to make the poor richer vs. making the rich poorer.

Now consider the public schools in the light of our success model. Relative improvement in any of the factors leading to success multiplies overall success. Relative improvement is easiest to achieve early on for those areas where the student is naturally interested and/or talented. Only after these areas have been saturated does it really pay to work on weaknesses.

So what do our schools do? They hold back students to the learning rate of their weaknesses. If you excel in math but poor in language, you get held back overall to match your language learning ability. If you are potentially brilliant artist, you still have to wait until high school to take a real art class. (This may not hold for the better schools.) If you are a natural athlete but poor academically, you aren't allowed to play on the varsity squad.

The power-nerd math genius should be taking advanced calculus in high school even as he is still mastering basic social skills and writing. The poet should be taking college level creative writing even as she struggles with basic algebra. The athlete from the ghetto might well take remedial public speaking and finance during the off season during his career years, after dropping out of college to make a multi-million dollar salary.

This doesn't mean the schools should allow children to focus only on their strengths. It means don't spend more time on the weaknesses than the strengths. It means let the talented leap forward in their particular skill areas while they muddle along in their areas of weakness.

Finally a personal application: promoting this very web site. Readership is a function of how many people find it times how interesting it is to them once they get here. Some Internet marketing experts write that I should spend more time promoting the site, getting links and the like, than producing the content itself. And they are right to first order. If I were to write articles elsewhere pointing to this site, commenting on other blogs, etc. readership would be much higher here than by my writing lengthy quality posts based on research and experiment. But I don't like link-building. So I write what I hope is good content (and the repeat visitor stats indicate someone likes this stuff), and spend less time promoting it. Eventually, there will be enough content to make it worth promoting even for me.

But I'm hoping for a higher order effect. If the quality is good enough, some of the visitors will do the linking for me. And if enough do so link, the search engines will bring in yet more visitors. Traffic will snowball. And this, my dear readers, points to two other important nonlinearties. We have more yet to explore regarding the real secret of the rich. Stay tuned.

Labels:

income distribution,

multiplier effects

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)